| |

|

|

| Turning the IT clock back 30 years |

|

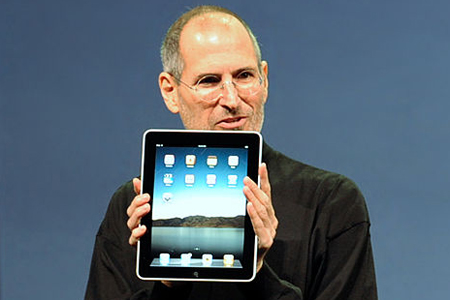

Photo: Matt Buchanan |

|

October 2011

After an amazing week in which the untimely death of an IT executive became the main marketing tool for a mobile phone upgrade, and now that California's Steve Jobs Day is behind us, I wonder when the man's legendary Reality Distortion Field will fade enough to allow a more sobre assessment of the Apple co-founder's legacy.

So much has been written by others that it's hard to know where to start. Someone could and probably has written a long article about all the things that Steve Jobs didn't invent, including the mouse, the tablet computer, the smartphone, copy and paste, wifi, the heart of the iPad's A4 processor... Very little of Apple technology was created ex nihilo. The entire Mac concept was demonstrated at Xerox PARC and could be found on Sun and Apollo workstations that were common in universities in the 1980s (although they were apparently invisible to the media). There's a sobre analysis of the Xerox/Apple link here. Siri, the Apple AI invention, was bought from elsewhere, which confirms Apple as a hugely rich multinational more than as creative pioneers.

Then there's what the BBC's obituary described as "... an ability to second guess the market and an eye for well designed and innovative products that everyone would buy." Yes... sometimes. If you want to play a cruel trick on your grieving mac-head friends, show them the photo of an Apple Newton, tell them it's made by Samsung, and watch them proclaim, tearfully, how Apple would never make such an unwieldy beast. The spectacular failure of that product probably put back tablet computing by half a decade. (If the Newton is too easy to spot, substitute the first iTunes phone). Then ask your friend how the latest attempt to launch AppleTV is working out, and when the social network called Ping is going to eclipse the popularity of, well, the average teenager's blog.

But as the dust and the adrenaline settle, I think Jobs' greatest achievement at this point is turning the IT clock back 30 years. I guess I might need to unpack that a bit.

In the beginning, there was the mainframe. The mainframe was huge, and expensive, and very hard to maintain. It dwelled in unapproachable air-conditioned rooms, and was protected by technicians who came to be known, loathingly, as IT high priests. The priests would enter the machine room, and then return to the underlings – sorry – users to present their admin decisions on tablets of stone.

Then came the minicomputer, which was small enough and cheap enough for some university or company departments to own. Then came the workstation, which was really a single-user minicomputer and was great if you could afford it. (The one I spent a year using cost £300k – thanks, MoD).

Then came the microcomputer, first as mail order kits that required soldering, then as slow, clunky consumer products like the Apple I and II, the Commodore Pet and the Acorn BBC Micro. The IT high priests laughed mightily... until finance departments began to run Visicalc spreadsheet software on their Apple microcomputers. And the IT high priests perceived revenue streams in the slow, clunky microcomputer, and did work mightily, and came up with the IBM PC that was even slower, even clunkier, and which took over the world thanks to IBM clones and Microsoft's operating system that ran on all those clones.

Ok, starting the PC revolution was the last thing IBM was trying to do. But, beyond the reality distortion field, paradigm changes are not scripted by a solitary genius. By losing control of both the hardware and the software, IBM inadvertantly created a new IT culture – a computing priesthood of all believers. No more admin policies, no more imposed decisions. If a team or a researcher wanted to do something different, it was suddenly possible to buy a computer from the petty cash and use it in deliciously unorthodox ways. The results often were and are ugly, but this was the period when everyone tried programming, even if it was just "10 print Hello: goto 10" on a display model of a ZX81.

This was the period when Excel spreadsheet macros looked like they could be used to solve any computing problem (which, incidentally, turns out to be true, at least in theory). The PC revolution was about wresting power from the IT high priests; about liberating the user underlings. PC expansion slots meant that every kind of exotic hardware was created to work alongside the software.

Before moving on, note that mainframes allowed large numbers of people do "be creative". They could write documents. They could do scientific calculations. Sometimes they could even write programs. But they did so under the – sometimes – benign watch of the IT priest caste who wielded total power within the IT world. In cultural terms, the PC revolution was largely about rejecting that hierarchical control.

IBM tried and failed to put the toothpaste back in the tube. Meanwhile, Apple's in-house creation, OS9, was as slow as molasses, liable to crash at any moment and thus threatened the very future of the entire company. (Re)-enter Steve Jobs with a plan to take BSD – a free version of the world's most popular workstation software – and make it look like OS9. Thus OSX was born, and with it the rebirth of Apple as the world's richest multinational.

(Incidentally, the co-creator of Unix, the operating system of which OSX is but one example, died shortly after Jobs. Ritchie also co-invented C, the programming language in which OSX and many other large programs are written. If you didn't know that, it's probably because his death received almost no media coverage.)

Success always breeds jealousy. Apple Inc II deserves credit for concentrating on "the user experience", and for spotting the point at which several technologies – such as mp3 players and smartphones – were ready to go mainstream. But, like a huge, multinational magic show, the product launches and the sales figures misdirected attention away from an underlying business plan which was and is to be more like IBM than IBM.

With iTunes, Jobs managed to gain a de facto monopoly of digital music, and used that monopoly to make iPods the only viable digital music player. (His later "conversion" to mp3 happened just as the music industry was beginning to realise it had been shafted, and after Apple had such a huge lead that it was going to be very hard for anyone else to catch up.)

With iPhone apps, Apple achieved an unprecedented level of control over the user's hardware. The old-school IT high priests could decide which programs ran in their organisation, and everyone complained. The Apple store allows Apple to decide which programs can run on every iPhone on the planet, and this was hailed as "freedom" and "creativity". It has been occasionally possible to hack iPhones, but the iOS5 "feature" that only allows updates directly from Apple via GSM may well put an end to that.

Apple identified the major technologies that allowed programmers to develop for more than one platform, and set out to destroy them. Flash was crippled on Apple computers and banned from iPhones, along with all scripting languages. Java support was sabotaged to a point where it became almost impossible to deploy Java software. (A subsequent deal with Oracle will eventually undo the sabotage, but the damage has already been done). And the app store is gradually gaining more control on the desktops too. It has taken a decade for the Internet to recover from Microsoft/Netscape browser wars. Steve Jobs can take more credit than most for recreating that disaster on mobile platforms.

Apple has also attempted to litigate the competition out of existence by aggressive use of sofware patents. If successful, Apple may yet ensure that software innovation becomes nigh-on impossible on any platform. Software patents are near the top of the list of concerns of most programmers, and they provide an excellent means to lock the developing world out of the digital revolution for the next generation. But because the issue is a bit techie, it remains virtually invisible in the mainstream and Christian media. And some of Apple's hardware "inventions" seem to boil down to patenting the rectangle. In a recent court case, Samsung submitted a clip from a classic sci-fi film to demonstrate that the iPad format really has been around for a while.

Even the most passionate Apple fan cannot fail to notice a whiff of control-freakery from time to time. But Steve Jobs continues to get a free pass on this because, apparently, it's ok to be a control freak if you are a genius who invented the mouse, the icon, the tablet computer and maybe the electron. The other justification is security, an argument which has worked well for dictators across the centuries. Security was also the justification for the IT high priest caste at the start of our story.

It is in this sense that Jobs has basically reinvented mainframe culture, now running on distributed hardware. And, to a large extent, he has managed to do so while keeping the Think different image. Making a huge, rich, controlling multinational look like hippy culture is a trick way more impressive than making an elephant disappear from a TV studio.

It has often been observed that dying too soon is a great way to create a personality cult. I'm sorry that Jobs is dead, and that he died relatively young. He made IT sexy, which was good for the entire industry. But I do wonder what history books will say about him in 10 or 25 years' time. I hope they will say that, at some point in our near future, the reality distortion field evaporated. I hope they will say we realised that choosing the colour of your desktop is not creativity, and that delegating the world's creativity to one multinational cannot possibly end well.

I hope it will still be legal to edit, read and distribute information on the hardware of our choice, using the software of our choice obtained from the source of our choice. And I hope that Christian discernment in these matters will have moved beyond rounded corners to issues such creativity, ownership and empowerment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Stephen Tomkins' regular column of tales of religious lunacy from the far reaches of the Net |

|

|

|

| Andrew Rumsey's regular column about the religious life |

|

|

|

| Stephen Tomkins' regular round-up of the saints of yore who were one wafer short of a full communion |

| |

|

|

|

|